Alcaraz's Torrid Pace

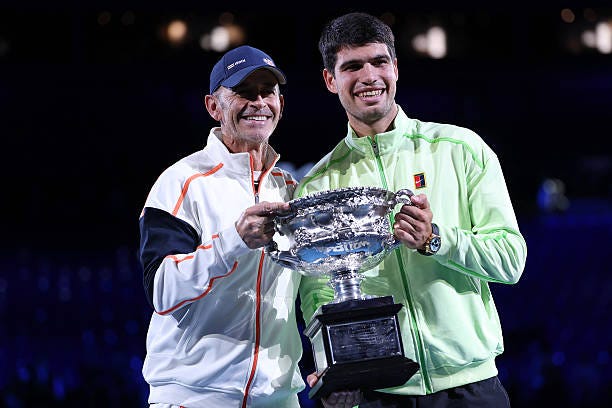

He claims the career Grand Slam at 22

Where there’s a will, there is not always a way.

For all Novak Djokovic’s craft and commitment, for all his happy memories in Australian Open finals, there was not quite enough fuel in the tank and precision in the strokes to beat two much younger superstars in a row.

Carlos Alcaraz, not Djokovic, was the history man on Sunday in Melbourne: becoming, at age 22, the youngest to complete the career Grand Slam.

Djokovic, at 38, could have become the oldest man to win a major singles title in the Open era and even had Ken Rosewall, the venerable Australian who holds that record, watching him from the stands. But Djokovic had to settle for a surprising and inspiring stretch run. That was, nonetheless, quite a consolation prize for the tennis champion who has everything, and it came with full-throated crowd support in a city that has not always embraced him.

“I always believe in myself, and I think it’s something that is truly needed and necessary when playing at this level against incredible players like Jannik and Carlos,” he told the crowd. “But I must be very honest and say I didn’t think I’d be standing in the closing ceremony of a Grand Slam once again, so I think I owe you the gratitude for pushing me forward the last couple of weeks.”

Djokovic’s five-set victory over Jannik Sinner in the semifinals belongs on his career short list, not too far behind his most memorable triumphs in majors. For a set against Alcaraz, he stayed on that roll: spryly dictating terms to the world No. 1, a man 16 years his junior, who is perhaps the quickest and most complete player in the game’s long history.

“I thought Novak was joking when he said he was thinking of playing the Olympics in ’28,” said John McEnroe on ESPN. “I’m not so sure right now.”

It was 6-2 in what felt like a rush. Djokovic made 78 percent of his first serves; hit eight winners, with the beefed-up forehand playing the leading role, and made just four unforced errors. His contact points were dead center of the strings. His serves were landing in the outside corners of the boxes, stretching Alcaraz into extreme positions that must have looked delightfully familiar to the elastic Djokovic.

On the set changeover, the amiable Alcaraz was fuming: gesticulating angrily at his team as he could not find what he was searching for in his racket bag.

A younger Alcaraz might not have shaken free of the tension and the trap. After all, he never did find the solution against an inspired Djokovic in their Roland Garros semifinal in 2023 or their Olympic gold-medal match in Paris in 2024 or their quarterfinal on this same blue hardcourt in Melbourne last year.

Djokovic, with his protean brilliance, can get in your head like nobody in tennis. Just ask Roger Federer or Rafael Nadal, who was sitting in the front row on Sunday night, watching intently in retirement as Alcaraz tried to solve the Serbian riddle that Nadal could never quite crack in Melbourne: not even after nearly six hours of supreme effort in the 2012 final.

But Alcaraz, as it turns out, is even more of a tennis prodigy than the precocious and ferocious Nadal. At 22, Nadal had six majors. At 22, Alcaraz now has seven and, while Nadal had to wait until he was 24 to complete his career Grand Slam at the 2010 US Open, Alcaraz already has ticked all four boxes.

It took him just 20 major appearances to manage it. It took Nadal 26. But let’s not get bogged down in too many numbers. Alcaraz is a treat to watch whether or not he is playing for history: a player whose speed, flair and variety keep not only opponents but spectators off balance.

Drop shot or big rip? He often does not know himself until the moment arrives, and his improvisational skills and agility helped change the equation on Sunday: not even a full-cut Djokovic backhand around the post could get past him.

But it seems fair to mention that Alcaraz has done so much so young with the benefit of a tool that previous prodigies could not access: open and frequent on-court coaching. It is now legal and has certainly helped him navigate the ebbs and flows of big matches against more experienced rivals: first with Juan Carlos Ferrero as his primary coach and now, after Ferrero’s surprise exit in the offseason, with Samuel Lopez in that role.

Lopez and Alcaraz’ s team helped him stay calm as he cramped against Alexander Zverev in the semifinals and nearly surrendered a two-set lead. On Sunday, which was also Lopez’s 56th birthday, he suggested that Alcaraz retreat to return second serves after the first set and also get more net clearance on his forehand.

That was sage advice, and it corresponded with a Djokovic dip. This was a chilly Australian Open final -- 58 degrees (14 Celsius) – and a windy one, too, even with the retractable roof far from wide open. From the start of the second set, Djokovic made more errors, missed more returns and first serves. Alcaraz took the hint and ran with it: extending rallies by covering the corners or ripping half volleys off Djokovic’s deep shots.

Alcaraz claimed the second set and then went in front for the first time by winning the fifth game of the third. The break point was a reminder of what separates Alcaraz from the pack. Djokovic hit a fine wide first serve that pulled the Spaniard well outside the doubles alley. But after Alcaraz’s forehand return, he was back at midcourt in a flash to punch a backhand from no-longer open space. The gaps close so quickly against Alcaraz, and the longest rallies began to go his way while Djokovic started to show signs of discomfort: touching his left calf between points and massaging his right hip on changeovers.

He called for the doctor and trainer after losing the third set and later declined to share details of what he had been experiencing: not wishing to detract from Alcaraz’s victory. But avoiding and managing injury is, of course, part of the recipe for success in tennis, and Djokovic’s body has worn and broken down more frequently under Grand Slam duress in the last three seasons as he has searched in vain for a 25th major.

So much went his way in Melbourne this year with Jakub Mensik withdrawing before their fourth-round match and Lorenzo Musetti retiring after winning the first two sets of their quarterfinal. It is hard to imagine Djokovic being quite so fresh again this late in a major, and he pounced on the opportunity to topple Sinner.

But he could do no more than threaten Alcaraz. He might have bedeviled him quite a bit longer if he had been able to convert a break point at 4-4 in the fourth set. But with a momentum shift in reach, he missed a relatively routine forehand to let Alcaraz get back to deuce. On the next point, the Spaniard cheated at physics: hooking a forehand winner crosscourt at a preposterously sharp angle. The hold would be his, and the title would soon follow, as he broke Djokovic in the 12th game with Djokovic missing more forehands on the final three points.

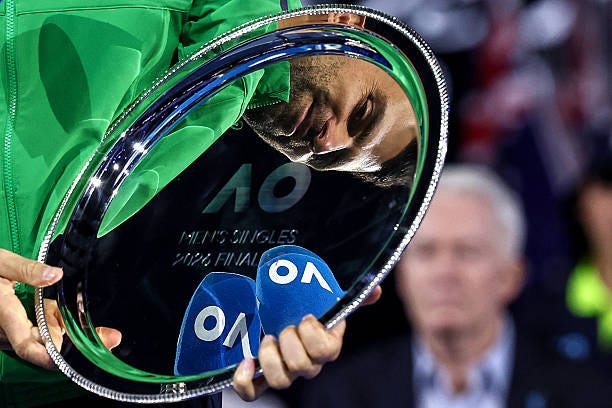

Final score: 2-6, 6-2, 6-4, 7-5.

Alcaraz, not Djokovic or Sinner, is the supreme big-match player of the moment. The youngster is 7-1 in major finals and 8-1 in ATP 1000 finals. He also has an astonishing 15-1 record in five-set matches that is far from a coincidence.

“Mental strength wins matches,” Alcaraz once said. “You don’t have to play brilliantly, show your best tennis or be the best version of yourself to win. In the end, you often win with your head. If you are mentally weak, you can lose even if you are playing the best tennis of your life. You can get through rounds, but when the key moment comes, if you are not strong in the head you won’t make it. In the fifth set of the final is the time to give it all, fight until you can’t fight anymore. That’s what makes you a warrior, and I consider myself a warrior.”

Djokovic can relate, but for the first time, he is an Australian Open runner-up after going undefeated in his first 10 finals. Nadal’s record of 14 singles titles at a major — his came at Roland Garros — seems ever more secure.

It was odd to see Djokovic, of all people, holding the silver finalist’s plate instead of the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup. It was nearly as strange to see Nadal applauding in the stands instead of clubbing forehands and fiddling with his shorts and water bottles.

“Obviously it feels very weird to see you there and not here,” Djokovic said in his runner-up speech to the man he faced 60 times on tour.

Djokovic finished with a 31-29 edge and also won the career head-to-head against Federer, Andy Murray, Stan Wawrinka and all of his leading peers. But he is now 5-5 against Alcaraz and trails Sinner 5-6.

It will only keep getting harder, no matter how ironclad the will. Though Djokovic has indeed talked about playing until the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles and has rightly railed against the constant retirement questions, he re-opened the door to speculation on Sunday night even if his performance would have been enough to keep it shut.

“God knows what happens tomorrow, let alone in six months or 12 months,” he told the crowd in Rod Laver Arena. “It has been a great ride. I love you guys!”

Another Australian Open sounds far from guaranteed, although if he can find this kind of form again this summer, winning an eighth Wimbledon is hardly out of the question.

He will be 39 by then, and Alcaraz, already a two-time Wimbledon champion himself, will be all of 23. On Sunday night, as Alcaraz posed for photos with the ballkids, the thought occurred that he was much closer to their ages than to the age of the man he had just faced.

Injury and complacency can be big obstacles. Precocity does not guarantee lasting supremacy. Who could have imagined Bjorn Borg stepping away at 25? But Alcaraz looked anything but burned out in Melbourne as he completed his Grand Slam collection and proved to himself and the chattering classes that he could win big without Ferrero.

He is setting a torrid early pace and already has as many major titles as John McEnroe, Mats Wilander and John Newcombe.

“Something tells me he’s going to be way past me,” McEnroe said.

CC

Thanks Chris. Your point about on-court coaching being a significant benefit and change for the "new" generation is well made. I thought the same with the women's final. The comments from the coaching box telling Rybakina to get her energy up turned the match around. A significant intervention. I wonder what would have happened if she had not received it? Personally, I am not a fan of this - I enjoyed the fact that players had to work out for themselves what they needed to do differently. That being said, I suppose one could argue that on-court coaching is no different to caddying!

Nice piece. Would have been impossible for McEnroe not to insert himself even while praising someone else. ... This may be a contrarian view, but the number of Alcaraz' Slams at his age seems more impressive than the career Slam. The differences between the Slams are so much smaller than they used to be. And most of the players have similar game styles. It's debatable which surface is best for Alcaraz, Djokovic or even Sinner. They're all great wherever they play. The conventional wisdom of six months ago that Sinner is better than Alcaraz on hard courts seems silly now. There's no current analog to Philippoussis vs. Agassi at 2003 Wimbledon or Tanner vs. Borg at 1979 U.S. Open. Don't get me wrong: Alcaraz could become the greatest ever. But it won't be because he overcame the difficulty of vastly different surfaces or of vastly different opponent skills.